As current critics recognize more renditions of Arabian tales converted to films, there seem to be many similar themes among them. In the stories of The Arabian Nights II I found many parallels to Zeman’s film, in that the seven voyages are sequentially presented as well as the theme of curiosity begging one to seek out adventure. Both show Sinbad as adventurous, setting to sea with a mind as though he has yet to experience the worst possible fate, though the book presents strongly Sinbad’s longing for trade and adventure which fulfills the notion that his “soul is naturally prone to evil.”1 In the film he’s much more humble, whereas the book shows him as a noble and proud character. Inferences to God and religion are more evident in the book, as he praises God for his good fortune and prays to be saved in times of danger. The film carries a greater theme of music and the soothing tune of the lute that calms Sinbad, much like the prayer does in the book, as he plays it after each new voyage and ends it right before his adventures take turn for the worse. Perhaps the film does not draw the repeated notion of religion from the book because of the uneasiness of the Czechoslovak government during that time. As important as faith is to the Mediterranean, particularly its Arabic origins, bringing it into a film while the nation was tense with citizens’ rebellion against the government might not go over so well with the media! Religion has a powerful hold on Sinbad and the book even reveals subtle imagery as symbols to his faith, when, during his seventh voyage, he witnesses fire drop from the sky. This presents his Deity as an almighty figure which controls his fate. Earlier in the fifth voyage, he describes a paradisiacal island where birds sing “of the Omnipotent, Everlasting One.”1 Interestingly enough, the birds also chirp to the whimsical song of Sinbad’s lute every time it is played throughout the film. In popular Czech animation, it’s commonplace to look “for the world’s reality…in the songs of birds.”3 Both music and religion are ultimately similar, represented in two different ways during his voyages. Each is mentioned at times of happiness as well as when the adventure turns. They take prevalence and power over Sinbad and act as underlying guides of his fate and the unraveling of the rest of the story to come.

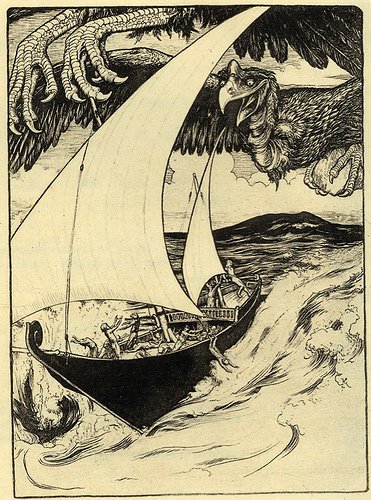

On the contrary, details such as the sultans and demons he encounters are fairly similar in both stories. The animals in the film befriend Sinbad, such as the birds that signal warnings and the first fish that was the cause of his fortune, and seem to guide him on his journey, as perhaps God is doing in the Nights II. Sinbad is protected by them, for the most part, even in times of supposed danger; for example, in the film, he takes shelter under wing of the giant Rukh that ends up unknowingly flying with him which scares Sinbad when he wakes, though he goes unnoticed and safely lands, evading capture. The book also tells of Sinbad hiding, but he remains awake because he is too afraid to fall asleep for fear of his death. Though he is safe after both situations, I got a sense that there is a greater connection between Sinbad and the animals, or perhaps natural environment in general, in the film version. The 1974 Golden Voyage of Sinbad also has similar themes of adventure and fortune given to those who do well.

Additionally, Sinbad’s character is a merchant in the book, while he is a sailor in the film. I’d like to think that being called just a sailor might infer his class as more commonplace, equal to the rest of his counterparts, as the united youth of Czechoslovakia, all fighting together as a community. Merchant, however, implies wealth and superiority, placing the character of Sinbad as something specialized and unlike the rest of his audience. As character occupations differ, the book Sinbad announces in several instances of self-blame, “you don’t learn, for every time you suffer hardships and weariness, yet you don’t repent and renounce travel in the sea, and when you renounce, you lie to yourself.”1 In the film, he has a true passion for the sea and feels a calling, not an obligation as in the book, where his desire lies in finding trade, after apparently having forgotten his previous horrible experiences. In the film he pushes on because of shear will and want to explore the unknown, which I believe describer a truer adventure.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment