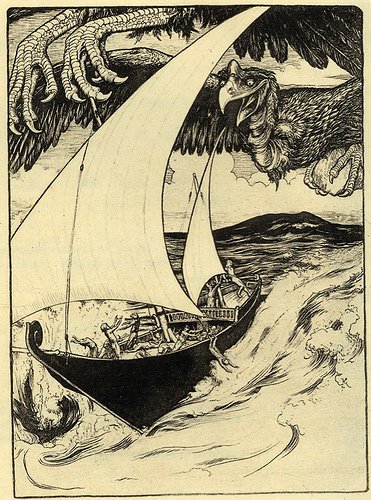

The Adventures of Sinbad the Sailor is a wonderfully animated film produced in Czechoslovakia in 1974 by a founding father of cinematic storytelling, Karel Zeman. Sinbad, a humble sailor who seeks adventure and new experiences on the sea, never losing hope despite forces against him which attempt to distract him from his own happiness. As Sinbad journeys to various islands, he just as often encounters misfortune, but his initial deed of setting free a fish he caught comes to aid him in many ways. The fish is a presence in other animals which help Sinbad in times of trouble, as in warning cries signaling foretelling danger. And so as Sinbad helps others before himself, he is graciously served with fortune concluding each frame tale. His voyages include escaping a whale mistaken for an island, soaring under-wing of the monstrous bird, carrying an old-man on his back, blinding a hungry giant, finding an endless sac of gold that buries an island, and tricking a genie from greed. All the while, Sinbad performs selfless deeds, trusting his humility and putting others before himself which serves to benefit in the end.

As Sinbad is indeed modest, the repeated instances of his carrying the burdens of others, literally and physically, all exemplify his exploitation as a human. Yet, he succumbs and remains loyal to each request until he realizes he can bear no other burdens apart from his own. Though he helps each pursuer, they have taken advantage of him, and he grows more aware each time. Sinbad also encourages the safety and young love of many princesses and their suitors as he meets them, giving up what he has so that they may escape. And though he has only a small raft to sail the seas, he is happy and continues to play a song on his lute.

A Connection to History:

Before Karel Zeman’s The Adventures of Sinbad the Sailor came out in 1974 in Czechoslovakia, the government and society was at an intriguing time of power struggle and post-war liberalization. In mid-1960s “writers, scholars, and journalists…began denouncing the crimes of political terror and the constraints of censorship.”5 Industry rose as the population became more involved in the government, with many participating in anti-Soviet demonstrations and revolution of communism. The perspective was gradually turning to a near-socialist democracy that granted freedoms of expression that perhaps Zeman took liberty with in his creative animations. Though I didn’t relate any parts of the film to any direct governmental expression, I began to wonder if Sinbad’s burdens were representative of the burden felt by the Czechoslovakian community to conform. It was almost as if Sinbad was the underdog, and though he endured a deal of suppression and obstacle, he maintained strong will and fought for his independence. Maybe Zeman was placing himself as the figure of Sinbad, since he did indeed write the film in such a freestyle manner. The animated characters also reminded me slightly of biblical representations or figures. Perhaps it was simply the style of animation or could be likened to a new-found hope or faith in the society at the time, as they were gaining more of a voice. Religion was a very deep and intrinsic characteristic of the Mediterranean and likely was throughout Europe and the rest of Czechoslovakia.

On Related Productions:

Karel Zeman, director of the film, is likened to great animators of the past and especially of Czechoslovakia. Zeman was said to create “a timeless representation of prehistory, so it remains convincing even now”4 and perhaps his connection to the past links to his actual experience of the changing nation around him at the time he designed animated films. He could capture the sentiment because he lived through hardship followed by hope for the Czech community.

One of his most renowned and influential films is Journey to Prehistory, released in 1955, where he mixed imaginative media of live action with that of animation. To briefly summarize, the film follows a group of young boys who set out on a small boat, seeking adventure, which magically leads them back in time. Czech and other audiences alike fell in love with Zeman’s creative and colorful imagery because it took them out of place for a moment, as movies should, to experience something new and exciting. Sinbad, shares the same curiosity of the unknown, risk, and fortune.

In 1958, Zeman produced The Fabulous World of Jules Verne, another feature in which he mixed animation and live acting, which strongly emphasizes his zest for creativity in storytelling, much like the Arabic Nights tales were marvelous visions of tales. He carried out this passion, equally, in film. And interestingly enough, “when political situationwas at its darkest, Czechoslovakian animated film astonished the world.”2

While I watched Sinbad, the lively paper-like animation seems directed towards children, while the dialogue appeals more to adults. Talking animals and personification of other objects in the film are the fantastical whimsy of it. Older audiences, however, would likely notice symbolism in imagery such as the blinding of the eyes, which also provokes the theme of curiosity or desire for the unknown. It was evident the film would entertain children, but it seems equally pleasing for adults, a story for them to revert to their past, in the magnetic way Zeman lures us out of common reality. For this reason, it would make sense that animation was so popular during the Communist era in central Europe.

One of his most renowned and influential films is Journey to Prehistory, released in 1955, where he mixed imaginative media of live action with that of animation. To briefly summarize, the film follows a group of young boys who set out on a small boat, seeking adventure, which magically leads them back in time. Czech and other audiences alike fell in love with Zeman’s creative and colorful imagery because it took them out of place for a moment, as movies should, to experience something new and exciting. Sinbad, shares the same curiosity of the unknown, risk, and fortune.

In 1958, Zeman produced The Fabulous World of Jules Verne, another feature in which he mixed animation and live acting, which strongly emphasizes his zest for creativity in storytelling, much like the Arabic Nights tales were marvelous visions of tales. He carried out this passion, equally, in film. And interestingly enough, “when political situationwas at its darkest, Czechoslovakian animated film astonished the world.”2

While I watched Sinbad, the lively paper-like animation seems directed towards children, while the dialogue appeals more to adults. Talking animals and personification of other objects in the film are the fantastical whimsy of it. Older audiences, however, would likely notice symbolism in imagery such as the blinding of the eyes, which also provokes the theme of curiosity or desire for the unknown. It was evident the film would entertain children, but it seems equally pleasing for adults, a story for them to revert to their past, in the magnetic way Zeman lures us out of common reality. For this reason, it would make sense that animation was so popular during the Communist era in central Europe.

Links to "The Arabian Nights" stories:

As current critics recognize more renditions of Arabian tales converted to films, there seem to be many similar themes among them. In the stories of The Arabian Nights II I found many parallels to Zeman’s film, in that the seven voyages are sequentially presented as well as the theme of curiosity begging one to seek out adventure. Both show Sinbad as adventurous, setting to sea with a mind as though he has yet to experience the worst possible fate, though the book presents strongly Sinbad’s longing for trade and adventure which fulfills the notion that his “soul is naturally prone to evil.”1 In the film he’s much more humble, whereas the book shows him as a noble and proud character. Inferences to God and religion are more evident in the book, as he praises God for his good fortune and prays to be saved in times of danger. The film carries a greater theme of music and the soothing tune of the lute that calms Sinbad, much like the prayer does in the book, as he plays it after each new voyage and ends it right before his adventures take turn for the worse. Perhaps the film does not draw the repeated notion of religion from the book because of the uneasiness of the Czechoslovak government during that time. As important as faith is to the Mediterranean, particularly its Arabic origins, bringing it into a film while the nation was tense with citizens’ rebellion against the government might not go over so well with the media! Religion has a powerful hold on Sinbad and the book even reveals subtle imagery as symbols to his faith, when, during his seventh voyage, he witnesses fire drop from the sky. This presents his Deity as an almighty figure which controls his fate. Earlier in the fifth voyage, he describes a paradisiacal island where birds sing “of the Omnipotent, Everlasting One.”1 Interestingly enough, the birds also chirp to the whimsical song of Sinbad’s lute every time it is played throughout the film. In popular Czech animation, it’s commonplace to look “for the world’s reality…in the songs of birds.”3 Both music and religion are ultimately similar, represented in two different ways during his voyages. Each is mentioned at times of happiness as well as when the adventure turns. They take prevalence and power over Sinbad and act as underlying guides of his fate and the unraveling of the rest of the story to come.

On the contrary, details such as the sultans and demons he encounters are fairly similar in both stories. The animals in the film befriend Sinbad, such as the birds that signal warnings and the first fish that was the cause of his fortune, and seem to guide him on his journey, as perhaps God is doing in the Nights II. Sinbad is protected by them, for the most part, even in times of supposed danger; for example, in the film, he takes shelter under wing of the giant Rukh that ends up unknowingly flying with him which scares Sinbad when he wakes, though he goes unnoticed and safely lands, evading capture. The book also tells of Sinbad hiding, but he remains awake because he is too afraid to fall asleep for fear of his death. Though he is safe after both situations, I got a sense that there is a greater connection between Sinbad and the animals, or perhaps natural environment in general, in the film version. The 1974 Golden Voyage of Sinbad also has similar themes of adventure and fortune given to those who do well.

Additionally, Sinbad’s character is a merchant in the book, while he is a sailor in the film. I’d like to think that being called just a sailor might infer his class as more commonplace, equal to the rest of his counterparts, as the united youth of Czechoslovakia, all fighting together as a community. Merchant, however, implies wealth and superiority, placing the character of Sinbad as something specialized and unlike the rest of his audience. As character occupations differ, the book Sinbad announces in several instances of self-blame, “you don’t learn, for every time you suffer hardships and weariness, yet you don’t repent and renounce travel in the sea, and when you renounce, you lie to yourself.”1 In the film, he has a true passion for the sea and feels a calling, not an obligation as in the book, where his desire lies in finding trade, after apparently having forgotten his previous horrible experiences. In the film he pushes on because of shear will and want to explore the unknown, which I believe describer a truer adventure.

On the contrary, details such as the sultans and demons he encounters are fairly similar in both stories. The animals in the film befriend Sinbad, such as the birds that signal warnings and the first fish that was the cause of his fortune, and seem to guide him on his journey, as perhaps God is doing in the Nights II. Sinbad is protected by them, for the most part, even in times of supposed danger; for example, in the film, he takes shelter under wing of the giant Rukh that ends up unknowingly flying with him which scares Sinbad when he wakes, though he goes unnoticed and safely lands, evading capture. The book also tells of Sinbad hiding, but he remains awake because he is too afraid to fall asleep for fear of his death. Though he is safe after both situations, I got a sense that there is a greater connection between Sinbad and the animals, or perhaps natural environment in general, in the film version. The 1974 Golden Voyage of Sinbad also has similar themes of adventure and fortune given to those who do well.

Additionally, Sinbad’s character is a merchant in the book, while he is a sailor in the film. I’d like to think that being called just a sailor might infer his class as more commonplace, equal to the rest of his counterparts, as the united youth of Czechoslovakia, all fighting together as a community. Merchant, however, implies wealth and superiority, placing the character of Sinbad as something specialized and unlike the rest of his audience. As character occupations differ, the book Sinbad announces in several instances of self-blame, “you don’t learn, for every time you suffer hardships and weariness, yet you don’t repent and renounce travel in the sea, and when you renounce, you lie to yourself.”1 In the film, he has a true passion for the sea and feels a calling, not an obligation as in the book, where his desire lies in finding trade, after apparently having forgotten his previous horrible experiences. In the film he pushes on because of shear will and want to explore the unknown, which I believe describer a truer adventure.

Bibliography

1The Arabian Nights II. Trans. Husain Haddawy. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

2Hames, Peter. “Czechoslovakia: After the Spring.” In Post New Wave Cinema in the

Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Bloomington, IN: Indian University Press,

1989.

3Polt, Harriet R. “The Czechoslovak Animated Film.” Film Quarterly, Vol. 17, No. 3.

(Spring, 1964), pp. 31-40. University of California Press.

http://www.jstor.org/view/00151386/ap040017/04a00120/0? frame=noframe&userID=8635b41a@muohio.edu/01c0a8346a00501d4b14f&dpi=3&config=jstor.

4Velinger, Jan. “Karel Zeman - author of Czech animated films including the mixed-

animation classic 'Journey to the Beginning of Time'” Radio Praha (2006).

http://www.radio.cz/en/article/74358.

5Williams, Kieran. “Liberalization.” In The Prague Spring and its aftermath:

Czechoslovak politics, 1968-1970. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press,

1997.

2Hames, Peter. “Czechoslovakia: After the Spring.” In Post New Wave Cinema in the

Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Bloomington, IN: Indian University Press,

1989.

3Polt, Harriet R. “The Czechoslovak Animated Film.” Film Quarterly, Vol. 17, No. 3.

(Spring, 1964), pp. 31-40. University of California Press.

http://www.jstor.org/view/00151386/ap040017/04a00120/0? frame=noframe&userID=8635b41a@muohio.edu/01c0a8346a00501d4b14f&dpi=3&config=jstor.

4Velinger, Jan. “Karel Zeman - author of Czech animated films including the mixed-

animation classic 'Journey to the Beginning of Time'” Radio Praha (2006).

http://www.radio.cz/en/article/74358.

5Williams, Kieran. “Liberalization.” In The Prague Spring and its aftermath:

Czechoslovak politics, 1968-1970. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press,

1997.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)